The Fabric of Reality Handbook

Basically a whole another book clearly and comprehensively explaining and summarizing The Fabric of Reality and its main ideas chapter by chapter.

🐣 0 — Introduction

A Word for Your Journey

I aim to concisely explain key points of the book, each chapter should take you around 30 minutes.

The best way to retain and incorporate ideas is to constantly challenge your understanding. Hence, chapters are structured by their main questions, after reading, you can practice them all as flashcards here.

I recorded summaries of all chapters as one podcast, you can listen to it above. You also can listen to my interview with Elias Schlie where we explore the main ideas of both The Beginning of Infinity, and The Fabric of Reality in 3 hours. Lastly, I made a public playlist with Brett Hall’s lectures in book’s order: you can listen to it here.

As a different medium you can read this handbook in Notion with toggled questions and chapters. (I’m working on a pdf version.)

The Fabric of Reality was a very rewarding and challenging read for me. I hope my work makes it easier to understand David’s ideas without diminishing their value. When in hardship — persevere, the fruits of understanding taste sweet.

My handbook is no substitute for reading the book, nothing is. It is a companion along your journey.

By endurance we conquer, Mark

🎯 5-Minute Summary

To change the world we first must understand it. To understand it we must take our best scientific theories seriously and jointly. These are: epistemology, quantum physics, computation and evolution.

All knowledge creation is a three-step process: meeting a problem, guessing a solution, and then, criticizing it. This is true for art, philosophy and math.

Since knowledge grows through criticism, we can never claim 100% certainty, as we don’t justify or create positive evidence for theories (even in mathematics).

Science wants to understand the world, which inescapably means explaining it. Prediction is a mean for criticizing theories, not an end on its own.

Explanations can’t be reduced to fundamental particles, for that is not an explanation at all. Good explanations invoke abstract and emergent phenomena.

Knowledge grows both in breadth (number of theories) and depth (scope of theories), the second one is winning. Thus, in the long-run all our theories will converge to one, that would be the theory of everything. It won’t be reductive, for good explanations invoke abstract and emergent phenomena. It also won’t be our last theory, since knowledge grows through criticism, not justification.

As we irreducibly use physical and abstract phenomena in our explanations, they both exist. For whether something is real or not depends on whether it is in our best explanations of the world.

Physical world provides a narrow window through which we observe the world of abstractions. Together they form the reality we are in.

Knowledge is a physical force, it can transform the landscape of Earth, and much more.

The only true constraints are laws of physics.

Everything they allow is achievable, the question is: How?

Knowledge is the answer.

Are things that create knowledge significant?

Their significance depends on knowledge power. With the right knowledge one can bend the universe to their will. Thus, things that create knowledge are universally significant.

Thus, life and humans are universally significant.

Evolution and epistemology both rely on variation and selection. This is for a reason, as the defining characteristic of life is knowledge creation and knowledge embodiment.

To those that seek explanations, quantum physics implies one thing loud and clear — reality is far bigger than we ever imagined, it consists of an infinite number of parallel universes which together form a multiverse. Every fiction that doesn’t violate laws of physics is a fact in the multiverse.

Quantum physics unlocks a qualitatively better mode of computation — quantum computers. They calculate intractable things for classical computers, and one cannot explain how they work without invoking parallel universes.

Computation is the process of calculating outputs from inputs by following some rules. Thus, a tree is a computer: its inputs are air, soil, and sun, by following genetic rules it is computing its output — growth and eventual death. Universe is a computer too: its input is the Big Bang, from which, by following the laws of physics it is computing its inevitable end.

Turing proved there can be a computer that can simulate any other computer — Universal Turing Machine. Thus, it can simulate anything in the universe arbitrarily well.

Universal Turing Machine doesn’t violate laws of physics, so it is built somewhere in the multiverse. Thus, laws of physics mandate their own understanding. Laws of physics mandate a knower.

So what would it take for reality to be understood? For knower to exist?

Only a bold guess that reality is understandable, and a relentless perseverance to make it such, fueled by blood, sweat and tears; all while staring straight into the deadliest beast of all — parochial social misconceptions, and fighting, fighting back; for there will be a knower — why not you?

My Favorite Quotes

understanding does not depend on knowing a lot of facts as such, but on having the right concepts, explanations and theories. — page 3

Prediction - even perfect, universal prediction - is simply no substitute for explanation. — page 5

To say that prediction is the purpose of a scientific theory is to confuse means with ends. It is like saying that the purpose of a spaceship is to burn fuel. In fact, burning fuel is only one of many things a spaceship has to do to accomplish its real purpose, which is to transport its payload from one point in space to another. Passing experimental tests is only one of many things a theory has to do to achieve the real purpose of science, which is to explain the world. — page 7

In reality, though, what happens is nothing like that. — page 41

Do not complicate explanations beyond necessity, because if you do, the unnecessary complications themselves will remain unexplained. — page 78

The Turing principle

It is possible to build a virtual-reality generator whose repertoire includes every physically possible environment. — page 135

If the laws of physics as they apply to any physical object or process are to be comprehensible, they must be capable of being embodied in another physical object - the knower. It is also necessary that processes capable of creating such knowledge be physically possible. Such processes are called science. — page 135

the laws of physics may be said to mandate their own comprehensibility. — page 135

CRYPTO-INDUCTIVIST: Yes. Please excuse me for a few moments while I adjust my entire world-view. — page 159

Inductivism is indeed a disease. It makes one blind. — page 165

one cannot predict the future of the Sun without taking a position on the future of life on Earth, and in particular on the future of knowledge. The colour of the Sun ten billion years hence depends on gravity and radiation pressure, on convection and nucleosynthesis. It does not depend at all on the geology of Venus, the chemistry of Jupiter, or the pattern of craters on the Moon. But it does depend on what happens to intelligent life on the planet Earth. It depends on politics and economics and the outcomes of wars. It depends on what people do: what decisions they make, what problems they solve, what values they adopt, and on how they behave towards their children. — page 184

To those who still cling to a single-universe world-view, I issue this challenge: explain how Shor’s algorithm works. I do not merely mean predict that it will work, which is merely a matter of solving a few uncontroversial equations. I mean provide an explanation. When Shor’s algorithm has factorized a number, using 10^500 or so times the computational resources that can be seen to be present, where was the number factorized? There are only about 10^80 atoms in the entire visible universe, an utterly minuscule number compared with 10^500. So if the visible universe were the extent of physical reality, physical reality would not even remotely contain the resources required to factorize such a large number. Who did factorize it, then? How, and where, was the computation performed? — page 217

the fabric of physical reality provides us with a window on the world of abstractions. It is a very narrow window and gives us only a limited range of perspectives. — page 255

Necessary truth is merely the subject-matter of mathematics, not the reward we get for doing mathematics. — page 253

they violate a basic tenet of rationality - that good explanations are not to be discarded lightly. — page 331

In view of all the unifying ideas that I have discussed, such as quantum computation, evolutionary epistemology, and the multiverse conceptions of knowledge, free will and time, it seems clear to me that the present trend in our overall understanding of reality is just as I, as a child, hoped it would be. Our knowledge is becoming both broader and deeper, and, as I put it in Chapter 1, depth is winning. But I have claimed more than that in this book. I have been advocating a particular unified world-view based on the four strands: the quantum physics of the multiverse, Popperian epistemology, the Darwin-Dawkins theory of evolution and a strengthened version of Turing’s theory of universal computation. It seems to me that at the current state of our scientific knowledge, this is the ‘natural’ view to hold. It is the conservative view, the one that does not propose any startling change in our best fundamental explanations. Therefore it ought to be the prevailing view, the one against which proposed innovations are judged. That is the role I am advocating for it. I am not hoping to create a new orthodoxy; far from it. As I have said, I think it is time to move on. But we can move to better theories only if we take our best existing theories seriously, as explanations of the world. — page 366

Find more quotes under the footnote.1

Found Mistakes?

This handbook will always be a work-in-progress. Yet, from now on I expect most of the future improvements to come from you — readers.

If you: find any mistakes, or have a better phrasing, or have a better example, or can think of any other improvement: comment below and I will update the handbook!

The beauty of internet as a medium is that you can easily correct and improve things. I want this handbook to stand the test of time, and become a timeless resources for all who are learning ideas of David.

Comment your proposals, I’ll review them all!

My Book Review

My goal for the first three month of the Self-Education year was to establish firm knowledge foundation. I couldn’t hope for a better companion than The Fabric of Reality. If you want to change the world you first must understand it, and this book is a great starting point.

For someone who spend 400 hours on it I won’t say something unexpected. Obviously this is a masterpiece, obviously this is the best book I’ve ever read on par with The Beginning of Infinity.

It changed me as a person.

It demystified the world.

It revealed interesting questions.

I’ve changed my life, my expectations and my desires to pursue some of them.

David brought so much value to me that I had to give something back. This is my attempt.

⭕ 1 — The Theory of Everything

It seems impossible for someone to know everything that is known nowadays, but is that so? Only if one believes it is about memorizing facts. Knowledge is a matter of understanding. It relies on good explanations, not myriad of facts. Good explanations are hard to come by, which is for the best for only a few must be taken seriously.

In this chapter David refutes instrumentalism and reductionism. He outlines an important thesis of the book: knowledge grows both in depth and breadth, but depth is winning. Thus, eventually one theory will encompass everything we know, from math to psychology. That would be The Theory of Everything.

1.1 On fallibility:

This would not be our last discovery, for our knowledge is fallible and we will always improve upon it. It will be one of the first such theories.

Summary

{I rarely use David’s chapter summaries, but this one is great.}

Scientific knowledge, like all human knowledge, consists primarily of explanations. Mere facts can be looked up, and predictions are important only for conducting crucial experimental tests to discriminate between competing scientific theories that have already passed the test of being good explanations. As new theories supersede old ones, our knowledge is becoming both broader (as new subjects are created) and deeper (as our fundamental theories explain more, and become more general). Depth is winning. Thus we are not heading away from a state in which one person could understand everything that was understood, but towards it. Our deepest theories are becoming so integrated with one another that they can be understood only jointly, as a single theory of a unified fabric of reality. This Theory of Everything has a far wider scope than the ‘theory of everything’ that elementary particle physicists are seeking, because the fabric of reality does not consist only of reductionist ingredients such as space, time and subatomic particles, but also, for example, of life, thought and computation. The four main strands of explanation which may constitute the first Theory of Everything are:

quantum physics Chapters 2, 9, 1 1, 12, 13, 14

epistemology Chapters 3, 4, 7, 10, 13, 14

the theory of computation Chapters 5, 6, 9, 10, 13, 14

the theory of evolution Chapters 8, 13, 14

— Page 30

You can practice chapter questions as flashcards here.

Understanding and Scientific Theories

1.1.0 What composes understanding? Explain on planetary motions.

Being able to predict, how ever accurate, does not equal understanding. One can memorize the archives and make ‘accurate’ predictions. Does it mean one understands planetary motions? No. One can memorize the formula and make accurate predictions of infinitely more scenarios. Does a higher number of accurate predictions equal understanding? No.

Planetary motions are understood when they are explained. Good theories have deep explanations and accurate predictions in one.

understanding does not depend on knowing a lot of facts as such, but on having the right concepts, explanations and theories. …

Being able to predict things or to describe them, however accurately, is not at all the same thing as understanding them. …

even though the formula summarizes infinitely more facts than the archives do, knowing it does not amount to understanding planetary motions. Facts cannot be understood just by being summarized in a formula, any more than by being listed on paper or committed to memory. They can be understood only by being explained. Fortunately, our best theories embody deep explanations as well as accurate predictions. For example, the general theory of relativity explains gravity in terms of a new, four-dimensional geometry of curved space and time. It explains precisely how this geometry affects and is affected by matter. That explanation is the entire content of the theory; predictions about planetary motions are merely some of the consequences that we can deduce from the explanation. —page 3

1.1.1 What is an explanation?

We all intuitively know, but defining it precisely is hard. It is about the why, not what and it seems to be a unique function of a human brain.

Roughly speaking, they are about ‘why’ rather than ‘what’; about the inner workings of things; about how things really are, not just how they appear to be; about what must be so, rather than what merely happens to be so; about laws of nature rather than rules of thumb. They are also about coherence, elegance and simplicity, as opposed to arbitrariness and complexity, though none of those things is easy to define either. — page 11

1.2.0 What are the three most valuable attributes of a scientific theory?

First, it explains an underlying truth that we cannot experience directly. Science explains seen in terms of unseen. Earth’s mass and curvature of spacetime explains why apple falls.

Second, scientific theories have both explanatory and predictive power, with the former we change the world. General relativity’s explanation of spacetime helps us to build spaceships and GPS navigation.

Third, a good scientific theory has a universal reach — beyond what is currently known. General relativity entirely explains quasars, yet they were discovered only 30 years after Einstein’s work. [1.1]

Similarly, when I say that I understand how the curvature of space and time affects the motions of planets, even in other solar systems I may never have heard of, I am not claiming that I can call to mind, without further thought, the explanation of every detail of the loops and wobbles of any planetary orbit. What I mean is that I understand the theory that contains all those explanations, and that I could therefore produce any of them in due course, given some facts about a particular planet. Having done so, I should be able to say in retrospect, ‘Yes, I see nothing in the motion of that planet, other than mere facts, which is not explained by the general theory of relativity.’ We understand the fabric of reality only by understanding theories that explain it. And since they explain more than we are immediately aware of, we can understand more than we are immediately aware that we understand. — page 12

1.3.0 Where are usually the main improvements between successive theory? Explain on general relativity and Newtonian physics.

The main difference with successive theory lies in explanations. General relativity’s predictions of planetary motions is a shade better than Newton’s theory, yet its explanatory power is unrivaled. Better explanations unlock creation of previously inaccessible technologies, like [GPS navigation](https://www.gpsworld.com/inside-the-box-gps-and-relativity/#:~:text=Advances in space-qualified atomic,nanosecond level to its users.).

1.2 On predictive power.

Don’t underestimate improvement in predictive power: general relativity predictions of black holes behavior is significantly better than Newtonian physics. [1.2]

the general theory of relativity explains gravity in terms of a new, four-dimensional geometry of curved space and time. It explains precisely how this geometry affects and is affected by matter. That explanation is the entire content of the theory; predictions about planetary motions are merely some of the consequences that we can deduce from the explanation.

What makes the general theory of relativity so important is not that it can predict planetary motions a shade more accurately than Newton’s theory can, but that it reveals and explains previously unsuspected aspects of reality, such as the curvature of space and time. — page 3

Instrumentalism and Reductionism

1.4.0 What is instrumentalism?

The view that the basic purpose of science is to predict an experiment, not to explain the reality. Explanations for instrumentalists are no more than psychological props — empty words.

The important thing is to be able to make predictions about images on the astronomers’ photographic plates, frequencies of spectral lines, and so on, and it simply doesn’t matter whether we ascribe these predictions to the physical effects of gravitational fields on the motion of planets and photons [as in pre-Einsteinian physics] or to a curvature of space and time. — Gravitation and Cosmology, page 147

1.4.1 What is the criticism of instrumentalism?

Science aims to understand reality, not merely predict it. Imagine we are given an oracle that can predict an outcome of any experiment but provides no explanation. For instrumentalists, science would be over!

First, we would be interested in how an oracle works. Second, how would it help us to build a better spaceship? Oracle could be used to test our design, not create it. If it fails it wouldn’t tell us why, just as with physical world. The **oracle is no different, it would only save us time and expenses on building a spaceship. Explaining the failure and improving the design would be on us, it would require understanding.

1.3 On predicting a fair roulette.

One can also consider a fair roulette. It would be impossible to predict, but does it mean that science can’t understand it? Certainly not. With good explanation one can understand why predicting a fair roulette is impossible.

Prediction - even perfect, universal prediction - is simply no substitute for explanation. — page 5

1.4.2 If wrong, why instrumentalism is so popular in academia?

It sounds superficially plausible because prediction is required to refute theories. It is a necessary part of the scientific method, but not its goal.

To say that the purpose of science is to make predictions is to confuse means with ends. Is the purpose of a spaceship to burn fuel? It is not. Its purpose is to travel from point A to point B and carry some load. The purpose of science is to explain the world and we do so by testing predictions of our most promising theories. {Want to remind yourself what is the scientific method? Review card 3.3.1}

although prediction is not the purpose of science, it is part of the characteristic method of science. The scientific method involves postulating a new theory to explain some class of phenomena and then performing a crucial experimental test, an experiment for which the old theory predicts one observable outcome and the new theory another. One then rejects the theory whose predictions turn out to be false. Thus the outcome of a crucial experimental test to decide between two theories does depend on the theories’ predictions, and not directly on their explanations. This is the source of the misconception that there is nothing more to a scientific theory than its predictions. — page 6

1.5.0 We reject theories by testing their predictions. Is this the only process by which we can grow scientific knowledge?

No. Many theories are rejected because they have bad explanations. Consider a theory that eating a kilo of grass will cure a common cold. This theory never gets to the experimental testing phase because it has no good explanation in the first place, so we never bother to test it.

1.5 On good explanations.

In The Beginning of Infinity David introduces a criterion for rejecting theories alike: bad theories have explanations that are easy to vary. Refer to The Beginning of Infinity, page 22.

experimental testing is by no means the only process involved in the growth of scientific knowledge. The overwhelming majority of theories are rejected because they contain bad explanations, not because they fail experimental tests. We reject them without ever bothering to test them. For example, consider the theory that eating a kilogram of grass is a cure for the common cold. That theory makes experimentally testable predictions: if people tried the grass cure and found it ineffective, the theory would be proved false. But it has never been tested and probably never will be, because it contains no explanation - either of how the cure would work, or of anything else. — page 7

1.6.0 What is reductionism?

The view that science always explains things reductively — analyzing them into smaller components and appealing to past events as causes.

1.6.1 What is the criticism of reductionism?

First, it disregards emergence — sometimes low-level complexity yields high-level simplicity. For instance a cat is easier to predict and explain, than an interaction of trillions of atoms.

Second, it believes that knowledge is always created by breaking down things into smaller components. However, this is false, we frequently understand things by appealing to high-level sciences.

Let’s consider a particular copper atom at the tip of the nose of Winston Churchill’s statue in London. Why is it there? Breaking down the statue to its subatomic particles and trying to explain their position by previous particle interactions only leads to an infinite regress. Eventually we would arrive at the Big Bang, yet, we would still have no explanation or understanding of why that copper atom is there. Nonetheless, if we appeal to history and culture (emergent phenomena) the why is rather obvious:

It is because Churchill served as prime minister in the House of Commons nearby; and because his ideas and leadership contributed to the Allied victory in the Second World War; and because it is customary to honour such people by putting up statues of them; and because bronze, a traditional material for such statues, contains copper, and so on. — page 22

{1.6 For more details watch this.}

Third, reductionism assumes that knowledge is always created by appealing to earlier events (i.e. stating causes). Yet, this is false even in fundamental physics! How could we know so much about the initial state of the universe if we have no idea of what was before it? How could we understand the time so well?! What was before it?

The Theory of Everything

1.7.0 What is the structure of science?

Reductionism assumes that low-level sciences are more important than high-level ones, but that is false. They both help us to understand and explain the world. One should search and accept a good explanation regardless of its scientific level. [1.3]

1.8.0 What David means by the Theory of Everything?

David believes that eventually our explanations of the world will converge to a single theory of everything that is understood by us. It would contain every known subject: math, physics, epistemology, history and so on. It won’t be reductive, as explanations can be found on many levels of reality.

The Theory of Everything would not encompass everything there is. Our knowledge is fallible, thus we’ll never approach this ideal (This is why David’s last book is called The Beginning of Infinity!). Hence, it also won’t be our last theory, for we will always be wrong and improve upon it.

1.8.1 Why will knowledge eventually converge to a single theory?

Knowledge is growing both in depth and breadth. Yet, with the accumulation of theories many render their usefulness and are replaced by singular deeper explanations. In the long run, those will converge to and we will have a unified theory of reality.

So, even though our stock of known theories is indeed snow balling, just as our stock of recorded facts is, that still does not necessarily make the whole structure harder to understand than it used to be. For while our specific theories are becoming more numerous and more detailed, they are continually being ‘demoted’ as the understanding they contain is taken over by deep, general theories. And those theories are becoming fewer, deeper and more general. By ‘more general’ I mean that each of them says more, about a wider range of situations, than several distinct theories did previously. By ‘deeper’ I mean that each of them explains more embodies more understanding - than its predecessors did, combined. — page 13

Consider building a house or a cathedral. Centuries ago we would require multiple master builders that have studied for decades to acquire general rules of thumb and intuitions. Each of them would be highly specialized, applying their skills to even slightly different problems would yield hopelessly wrong answers. Nonetheless, any architect nowadays studies not only less, but also can solve wide ranging problems, for he is relying on deep theories of reality, which are universally applicable.

Progress to our current state of knowledge was not achieved by accumulating more theories of the same kind as the master builder knew. Our knowledge, both explicit and inexplicit, is not only much greater than his but structurally different too. As I have said, the modern theories are fewer, more general and deeper. For each situation that the master builder faced while building something in his repertoire - say, when deciding how thick to make a load bearing wall - he had a fairly specific intuition or rule of thumb, which, however, could give hopelessly wrong answers if applied to novel situations. Today one deduces such things from a theory that is general enough for it to be applied to walls made of any material, in all situations: on the Moon, underwater, or wherever. The reason why it is so general is that it is based on quite deep explanations of how materials and structures work. …

That is why, despite understanding incomparably more than an ancient master builder did, a modern architect does not require a longer or more arduous training. A typical theory in a modern student’s syllabus may be harder to understand than any of the master builder’s rules of thumb; but the modern theories are far fewer, and their explanatory power gives them other properties such as beauty, inner logic and connections with other subjects which make them easier to learn. Some of the ancient rules of thumb are now known to be erroneous, while others are known to be true, or to be good approximations to the truth, and we know why that is so. A few are still in use. But none of them is any longer the source of anyone’s understanding of what makes structures stand up. — page 14

1.8.2 What this implies?

More knowledge does not equal more theories. This grand unification will make it only more feasible to understand everything that is understood.

Our best theories might be harder to understand than rules of thumb, but this is not a significant barrier. Theory’s depth has no correlation with its complexity, in fact, frequently consolidation makes it only easier to understand. Consider electromagnetism:

a new theory may be a unification of two old ones, giving us more understanding than using the old ones side by side, as happened when Michael Faraday and James Clerk Maxwell unified the theories of electricity and magnetism into a single theory of electromagnetism. More indirectly, better explanations in any subject tend to improve the techniques, concepts and language with which we are trying to understand other subjects, and so our knowledge as a whole, while increasing, can become structurally more amenable to being understood. — page 9

🎞️ 2 — Shadows

In this chapter David explains the basis of quantum physics — an experiment from which we infer there are parallel universes (and why physicist refer to it as a multiverse). This conclusion is accessible to those that seek explanations, not predictions.

Summary

Light is made out of smallest discrete particles called photons. In fact, quantum physics states that all matter is made out of smallest inseparable particles.

Does light travel in straight lines only? On a bigger scale it does, for we cannot see around the corners, but when constrained to smaller sizes it bends.

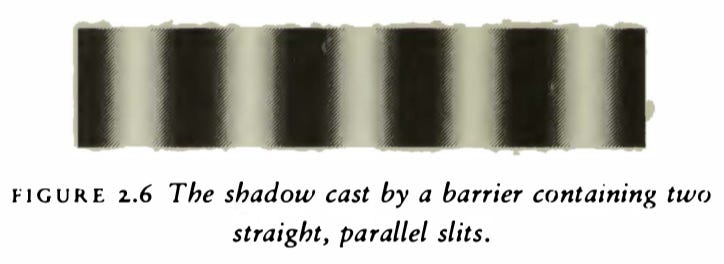

If you put two slits and shed light from them you’ll get an unusual striped shadows.

It’s weird, but not disturbing since we know that light bends on a smaller scale. We can explain the shadows by saying that photons bump with each other like billiard balls, interfering and producing the pattern.

What would happen if we send just one photon? The disturbing part is that with enough time we’ll get exactly the same pattern. But what could be interfering? We can put detector on each slit that goes off whenever a photon is passing by. Maybe our single photon splits and interfere with itself.

Yet, we always observe only one slit going off. So nothing detectable is passing through the other slits, and yet if close them we’ll get a different pattern. So something is passing through! We quickly find out that whatever is passing also behaves like light — it penetrates diamond, but not fog.

Such results repeat for every other element, not just light. To explain the interference of a singular photon we must say that there are additional ‘shadow’ photons travelling with it that we can’t see, yet they impact the one we can see. As the same is true for elements, we say there are additional ‘shadow’ elements for every one that is visible to us. Elements and photons, together form a universe. A parallel universe.

You can practice chapter questions as flashcards here.

Properties of Light

2.1.0 Imagine an infinite empty room with no light. What would you see if you turned on a flashlight in your hand?

Nothing; if light has no matter to reflect upon, it won’t arrive in your eye!

2.2.0 Let’s imagine there is someone 10km away from you — we’ll call him Bob. If you were to turn on the flashlight, is there a distance from which Bob would entirely lose sight of light?

There isn’t! Regardless of how far he walks away he would see light.

2.2.1 What exactly would he see?

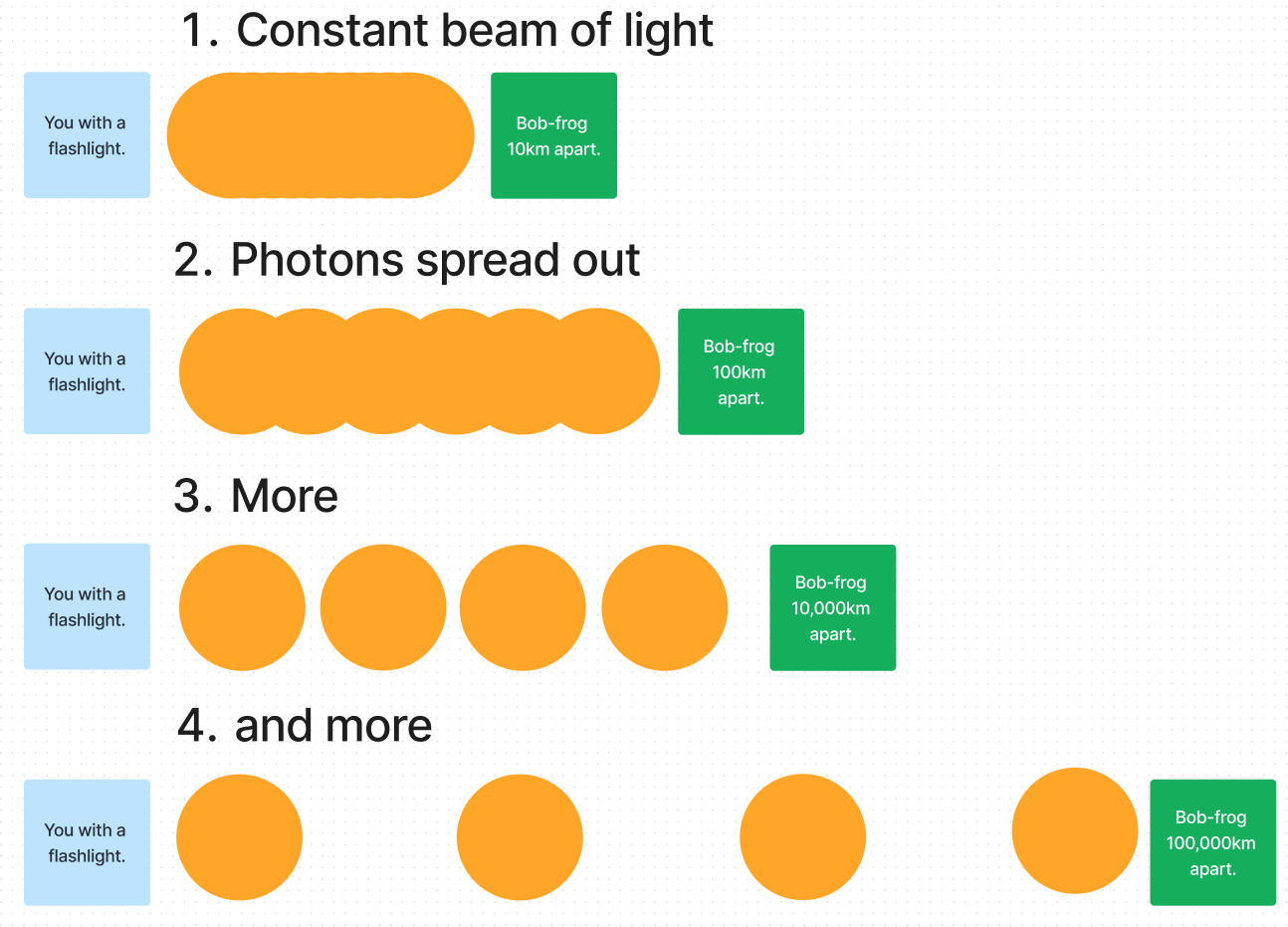

This requires a more detailed answer! First, I must confess, eventually Bob would lose sight because human eyes are not that sensitive to light. Nonetheless, if we turn Bob into a frog, than his eyes would be just right to always see light.

2.2.2 Would he see a constant stream of light?

This question highlights the fundamental difference between classical and quantum physics.

In classical physics matter is continuous — regardless of how much you ‘zoom-in’ you will never get to the smallest lump of something. Hence, there will always be a constant beam of light that never seizes to zero, yet the further you go, the tinier it gets. Thus, in classical physics you can spread light ever more thinly without a limit. Same holds for matter, a sheet of gold could be spread thinner and thinner without an end.

In quantum physics it is the other way around. Quantum literally means the smallest lump of something. Everything can be broken down into the smallest parts, but no smaller, and hence, everything (both light and matter) appear in chunks of discrete sizes.

2.2.3 So what would Bob-frog see?

Quantum physics states that light is made out of the smallest discrete units — photons. So once Bob-frog gets far enough, he won’t see a constant beam, he would see a flickering of photons. The further he goes, the more periodic they are. But brightness would stay the same, as it is always one photon!

The photons stay the same, yet as you move away their frequency decreases:

Not to scale!

The same idea applies for a sheet of gold:

the only way in which one can make a one-atom-thick gold sheet even thinner is to space the atoms farther apart, with empty space between them. When they are sufficiently far apart it becomes misleading to think of them as forming a continuous sheet. For example, if each gold atom were on average several centimetres from its nearest neighbour, one might pass one’s hand through the ‘sheet’ without touching any gold at all. Similarly, there is an ultimate lump or ‘atom’ of light, a photon. Each flicker seen by the frog is caused by a photon striking the retina of its eye. …

When the beam is very faint it can be misleading to call it a ‘beam’, for it is not continuous. During periods when the frog sees nothing it is not because the light entering its eye is too weak to affect the retina, but because no light has entered its eye at all. — page 35

2.3.0 What is the quantization property?

The property of matter and light appearing only in lumps of discrete sizes. A single lump (like a photon) is called quantum.

This property of appearing only in lumps of discrete sizes is called quantization. An individual lump, such as a photon, is called a quantum (plural quanta). Quantum theory gets its name from this property, which it attributes to all measurable physical quantities - not just to things like the amount of light, or the mass of gold, which are quantized because the entities concerned, though apparently continuous, are really made of particles. — page 35

2.4.0 Our next two questions are directly taken from the book. Consider this picture:

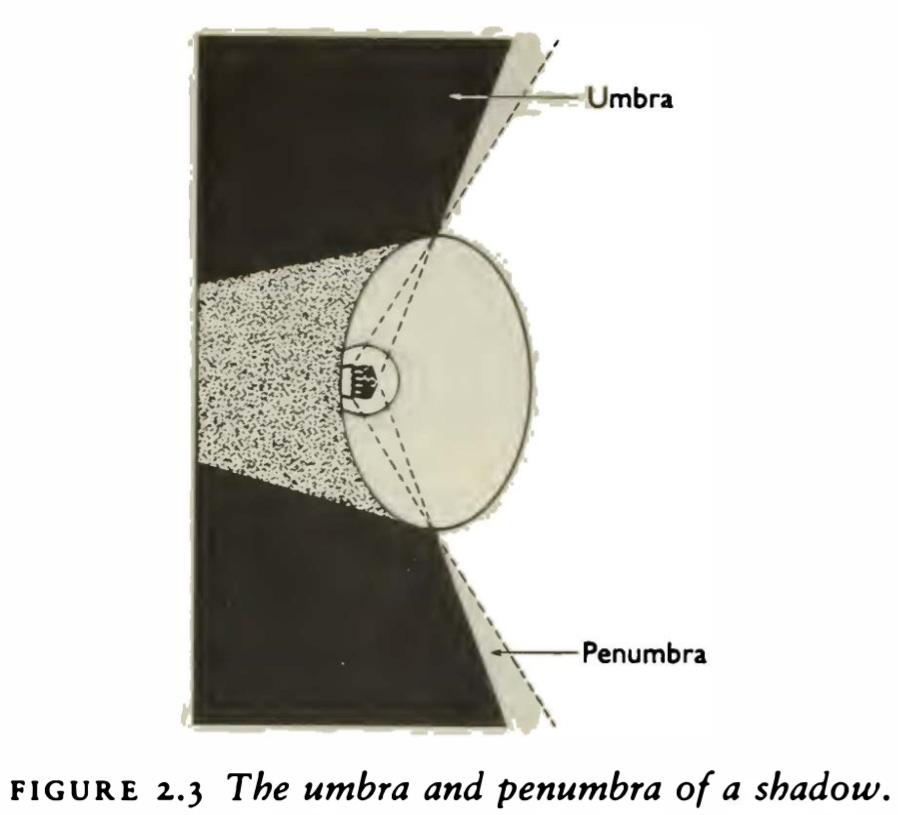

is there, in principle, any limit on how sharp a shadow can be (in other words, on how narrow a penumbra can be)? For instance, if the torch were made of perfectly black (non-reflecting) material, and if one were to use smaller and smaller filaments, could one then make the penumbra narrower and narrower, without limit? — page 36

2.4.0 Answer

Penumbra can get narrower only if light always travels in straight lines. In our daily life’s it does — for we cannot see around the corners! Yet, when confined to small sizes — it rebels.

2.4.1 Consider this picture:

if the experiment is repeated with ever smaller holes and with ever greater separation between the first and second screens, can one bring the umbra - the region of total darkness - ever closer, without limit, to the straight line through the centres of the two holes? Can the illuminated region between the second and third screens be confined to an arbitrarily narrow cone? — page 37

2.4.1 Answer

It cannot! The result is illustrated in the figure 2.5:

even with holes as large as a millimetre or so in diameter, the light begins noticeably to rebel. Instead of passing through the holes in straight lines, it refuses to be confined and spreads out after each hole. And as it spreads, it ‘frays’. The smaller the hole is, the more the light spreads out from its straight-line path. Intricate patterns of light and shadow appear. We no longer see simply a bright region and a dark region on the third screen, with a penumbra in between, but instead concentric rings of varying thickness and brightness. — page 38

When confined to small sizes light frays and bends; you might ask: “So what? It may be interesting, but fundamentally, it’s not disturbing”. And I agree, so let’s get to the disturbing part ;)

Double Slit Experiment

2.5.0 Imagine an opaque barrier that has two straight, parallel slits which are separated by 0.2 millimetres apart:

If we shed light through the slights we get unusual shadows, but they just verify our past conclusion (that light ‘rebels’ when constrained to small sizes):

Now, what sort of shadow is cast if we cut a second, identical pair of slits in the barrier, interleaved with the existing pair, so that we have four slits at intervals of one-tenth of a millimetre? — page 40

2.5.0 Answer

We might expect the pattern to look almost exactly like Figure 2.6. After all, the first pair of slits, by itself, casts the shadows in Figure 2.6, and as I have just said, the second pair, by itself, would cast the same pattern, shifted about a tenth of a millimetre to the side - in almost the same place. We even know that light beams normally pass through each other unaffected. So the two pairs of slits together should give essentially the same pattern again, though twice as bright and slightly more blurred.

In reality, though, what happens is nothing like that. — page 41

Figure 2.7 illustrates what happens, adding two more slides somehow darkens the point X:

2.5.1 What are possible explanations for this phenomena?

David proposes:

One might imagine two photons heading towards X and bouncing off each other like billiard balls. Either photon alone would have hit X, but the two together interfere with each other so that they both end up elsewhere. I shall show in a moment that this explanation cannot be true. Nevertheless, the basic idea of it is inescapable: something must be coming through that second pair of slits to prevent the light from the first pair from reaching X. But what? We can find out with the help of some further experiments. — page 41

We establish that whatever interferes with the shadows behaves like light:

First, the four-slit pattern of Figure 2.7(a) appears only if all four slits are illuminated by the laser beam. If only two of them are illuminated, a two-slit pattern appears. If three are illuminated, a three-slit pattern appears, which looks different again. So whatever causes the interference is in the light beam. The two-slit pattern also reappears if two of the slits are filled by anything opaque, but not if they are filled by anything transparent. In other words, the interfering entity is obstructed by anything that obstructs light, even something as insubstantial as fog. But it can penetrate anything that allows light to pass, even something as impenetrable (to matter) as diamond. If complicated systems of mirrors and lenses are placed anywhere in the apparatus, so long as light can travel from each slit to a particular point on the screen, what will be observed at that point will be part of a four-slit pattern. — page 42

2.5.2 What would then happen if we fire just one photon through two and four slits?

Interference is caused by something that behaves like a photon, hence, if we send just one it won’t happen. We might expect some new pattern to emerge, but what we should not see is some place on the screen (like X) that goes dark when two additional slits are opened (for that is an interference).

Yet. This is exactly what we observe.

Even when the experiment is done with one photon at a time, none of them is ever observed to arrive at X when all four slits are open. Yet we need only close two slits for the flickering at X to resume. — page 43

2.5.3 “Could it be that the photon splits into fragments which, after passing through the slits, change course and recombine?”— page 43

We can rule that possibility out too. If, again, we fire one photon through the apparatus, but use four detectors, one at each slit, then at most one of them ever registers anything. Since in such an experiment we never observe two of the detecters going off at once, we can tell that the entities that they detect are not splitting up. So, if the photons do not split into fragments, and are not being deflected by other photons, what does deflect them? When a single photon at a time is passing through the apparatus, what can becoming through the other slits to interfere with it? — page 43

2.5.4 Let’s revisit our findings so far.

We have found that when one photon passes through this apparatus,

it passes through one of the slits, and then something interferes with it,

deflecting it in a way that depends on what other slits are open;

the interfering entities have passed through some of the other slits;

the interfering entities behave exactly like photons ...

. . . except that they cannot be seen. — page 43

2.5.5 What can we infer from this?

Whatever interferences with our photon, behaves also like a photon, but we can’t detect it. For now, we’ll refer to it as ‘shadow photons’.

I shall now start calling the interfering entities ‘photons’. That is what they are, though for the moment it does appear that photons come in two sorts, which I shall temporarily call tangible photons and shadow photons. Tangible photons are the ones we can see, or detect with instruments, whereas the shadow photons are intangible (invisible) - detectable only indirectly through their interference effects on the tangible photons. — page 43

2.5.6 How many shadow photons accompany a tangible one?

The Fabric of Reality was published in 1997 and the lower bound was at one trillion shadow photons.

2.3 On number of universes.

It is either very very large number of infinite. Once you study the Multiverse chapter of The Beginning of Infinity you realize how this question seizes its meaning. There are no actual universes in our classical meaning of the word. It is one extremely large multiverse, that subjectively appears to consist of independent universes, but it’s all part of one structure.

Since different interference patterns appear when we cut slits at other places in the screen, provided that they are within the beam, shadow photons must be arriving all over the illuminated part of the screen whenever a tangible photon arrives. Therefore there are many more shadow photons than tangible ones. How many? Experiments cannot put an upper bound on the number, but they do set a rough lower bound. In a laboratory the largest area that we could conveniently illuminate with a laser might be about a square metre, and the smallest manageable size for the holes might be about a thousandth of a millimetre. So there are about 10^12 (one trillion) possible hole-locations on the screen. Therefore there must be at least a trillion shadow photons accompanying each tangible one. — page 44

2.5.7 Is the interference effect limited to photons only?

No, similar phenomena occur in every type of particle.

2.5.8 Considering our discussion above, what conclusion it implies?

there must be hosts of shadow neutrons accompanying every tangible neutron, hosts of shadow electrons accompanying every electron, and so on. Each of these shadow particles is detectable only indirectly, through its interference with the motion of its tangible counterpart.

It follows that reality is a much bigger thing than it seems, and most of it is invisible. The objects and events that we and our instruments can directly observe are the merest tip of the iceberg.

Now, tangible particles have a property that entitles us to call them, collectively, a universe. This is simply their defining property of being tangible, that is, of interacting with each other, and hence of being directly detectable by instruments and sense organs made of other tangible particles. Because of the phenomenon of interference, they are not wholly partitioned off from the rest of reality (that is, from the shadow particles). If they were, we should never have discovered that there is more to reality than tangible particles. But to a good approximation they do resemble the universe that we see around us in everyday life, and the universe referred to in classical (pre-quantum) physics. — page 44

2.5.9 So far we have inferred an existence of a ‘shadow universe’ which seems to be at least trillion times bigger than ours. How then, do we know that these shadow particles are actually grouped into parallel universes like ours?

We start with the fact that a tangible barrier is not influenced by a shadow photon. If we put a detector it never goes off, so the shadow photon can’t be stopped by it.

To put that another way, shadow photons and tangible photons are affected in identical ways when they reach a given barrier, but the barrier itself is not identically affected by the two types of photon. — page 46

What stops the shadow photon then? If it was anything from tangible atoms we could sense it. We know that every kind of particle has a shadow counterpart, thus it seems that shadow photons are stopped by shadow atoms (i.e. shadow barriers).

this shadow barrier is made up of the shadow atoms that we already know must be present as counterparts of the tangible atoms in the barrier. There are very many of them present for each tangible atom. Indeed, the total density of shadow atoms in even the lightest fog would be more than sufficient to stop a tank, let alone a photon, if they could all affect it. Since we find that partially transparent barriers have the same degree of transparency for shadow photons as for tangible ones, it follows that not all the shadow atoms in the path of a particular shadow photon can be involved in blocking its passage. Each shadow photon encounters much the same sort of barrier as its tangible counterpart does, a barrier consisting of only a tiny proportion of all the shadow atoms that are present.

For the same reason, each shadow atom in the barrier can be interacting with only a small proportion of the other shadow atoms in its vicinity, and the ones it does interact with form a barrier much like the tangible one. And so on. All matter, and all physical processes, have this structure. …

In other words, particles are grouped into parallel universes. They are ‘parallel’ in the sense that within each universe particles interact with each other just as they do in the tangible universe, but each universe affects the others only weakly, through interference phenomena. — page 46

2.6.0 In our explanations of parallel universes we have the idea of tangible universe and shadow universes. What exactly differentiates them?

Only its subjective point of view. Let’s come back to the example at the start of the chapter with our Bob-frog and a flashlight in an infinitely big dark room. We now know there are at least a trillion shadow universes with exactly the same Bob-frogs and flashlights as in our ‘tangible’ universe. But for them, their universe is tangible and ours is shadow. There is no inherent difference between the universes, just the subjective point of view.

Let’s also say that we asked Bob-frog to jump once he sees the flickering. Before we turn on a flashlight all universes are identical. Yet the precise time of its arrival varies, so the multiverse will start splitting depending on a photon and Bob-frog’s jump.

While I was writing that, hosts of shadow Davids were writing it too. They too drew a distinction between tangible and shadow photons; but the photons they called ‘shadow’ include the ones I called ‘tangible’, and the photons they called ‘tangible’ are among those I called ‘shadow’.

Not only do none of the copies of an object have any privileged position in the explanation of shadows chat I have just outlined, neither do they have a privileged position in the full mathematical explanation provided by quantum theory. I may feel subjectively that I am distinguished among the copies as the ‘tangible’ one, because I can directly perceive myself and not the others, but I must come to terms with the fact that all the others feel the same about themselves.

Many of those Davids are at this moment writing these very words. Some are putting it better. Others have gone for a cup of tea. — page 53

🔓 3 — Problem-solving

Claiming the existence of parallel universes is a radical world-view from any perspective. How do we know? How do we arrive at such conclusions? These questions are studied under epistemology — the main focus of this chapter.

David explains why inductivism is false, and what the true process of science is — Popperian epistemology. He also touches upon solipsism, which we’ll discuss in detail next time.

Summary

Empiricism is a philosophical view that we derive knowledge from our senses. It is wrong for it doesn’t explain how we choose what to observe, there are infinite things to look at, we can’t observe all at once.

Solipsism is a set of philosophical theories that say reality has some boundary, like matrix, or that it’s all a dream happening in your head.

Induction says that knowledge is created by pure observation and extrapolation of those observations. Observation can’t be pure for it is a mistake of empiricism. But the other problem is that it tries to justify theories by doing more observations. This is bad, for the same observation can ‘justify’ diametrically opposite theories.

Popperian epistemology comes to replace both empiricism and induction. It says that all knowledge creation is about problem-solving. You guess a solution to the problem and then criticize it, not try to prove it right.

Moreover, all our observations are based on our theories, so that solves the empiricism problem. Finally, since all knowledge is just a guess, and observations are based on theories (that can be wrong) — all our knowledge is fallible. We can never have a 100% certainty about anything, even that 2+2 is 4, for we use our brain that is fallible. Popper claims we never create a positive evidence for theory (like in induction), we can only criticize it.

You can practice chapter questions as flashcards here.

Empiricism, Solipsism and Induction

3.1.0 What is empiricism? What is its criticism?

Empiricism is a philosophical view that we derive knowledge from our senses. It is wrong for it doesn’t explain how out of infinite possible things to pay attention to, we choose one over the other. We must rely on something, it can’t be just pure observation, as there is too much to observe.

we do not directly perceive the stars, spots on photographic plates, or any other external objects or events. We see things only when images of them appear on our retinas, and we do not perceive even those images until they have given rise to electrical impulses in our nerves, and those impulses have been received and interpreted by our brains. Thus the physical evidence that directly sways us, and causes us to adopt one theory or world-view rather than another, is less than millimetric: it is measured in thousandths of a millimetre (the separation of nerve fibres in the optic nerve), and in hundredths of a volt (the change in electric potential in our nerves that makes the difference between our perceiving one thing and perceiving another). …

however sophisticated the instruments we use, and however substantial the external causes to which we attribute their readings, we perceive those readings exclusively through our own sense organs. There is no getting away from the fact that we human beings are small creatures with only a few inaccurate, incomplete channels through which we receive all information from outside ourselves. We interpret this information as evidence of a large and complex external universe (or multiverse). But when we are weighing up this evidence, we are literally contemplating nothing more than patterns of weak electric current trickling through our own brains.

What justifies the inferences we draw from these patterns? — page 57

3.2.0 What is solipsism?

Solipsism is a set of philosophical theories that claim that reality has some specific boundary. Some claim it is just a dream and nothing exist outside our mind, some claim the boundary around the Earth, our galaxy or matrix of some kind. This theories can be considered jointly because the ‘line’ is usually drawn arbitrarily, hence they can be refuted by the same means (which we’ll consider in the next chapter).

Solipsism, the theory that only one mind exists and that what appears to be external reality is only a dream taking place in that mind, cannot be logically disproved. Reality might consist of one person, presumably you, dreaming a lifetime’s experiences. Or it might consist of just you and me. Or just the planet Earth and its inhabitants. …

There is a large class of related theories here, but we can usefully regard them all as variants of solipsism. They differ in where they draw the boundary of reality (or the boundary of that part of reality which is comprehensible through problem-solving) , and they differ in whether, and how, they seek knowledge outside that boundary. But they all consider scientific rationality and other problem solving to be inapplicable outside the boundary - a mere game — page 58, 80

3.3.0 What is induction?

A philosophical view that knowledge creation happens by extrapolating or generalizing the results of observations.

3.3.1 What role observations play in this world-view?

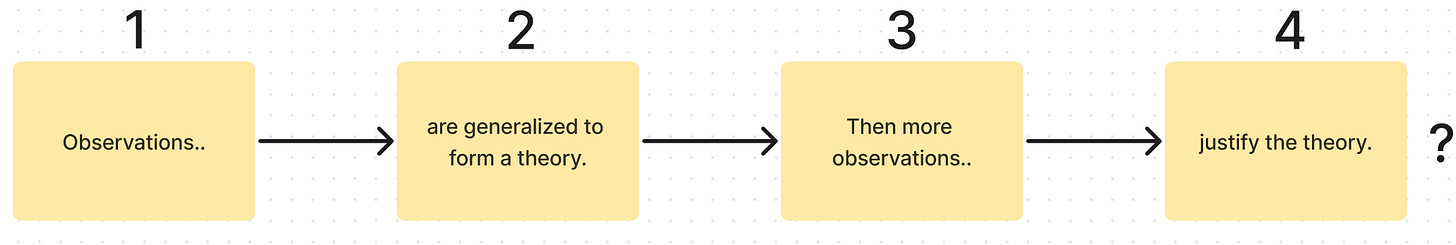

In the inductivist theory of scientific knowledge, observations play two roles: first, in the discovery of scientific theories, and second, in their justification. A theory is supposed to be discovered by ‘extrapolating’ or ‘generalizing’ the results of observations. — page 59

3.3.2 What are the stages of inductivism? Describe the knowledge creation process on the shadows example from the past chapter.

if large numbers of observations conform to the theory, and none deviates from it, the theory is supposed to be justified - made more believable, probable or reliable. … The inductivist analysis of my discussion of shadows would therefore go something like this: ‘We make a series of observations of shadows, and see interference phenomena (stage 1). The results conform to what would be expected if there existed parallel universes which affect one another in certain ways. But at first no one notices this. Eventually (stage 2) someone forms the generalization that interference will always be observed under the given circumstances, and thereby induces the theory that parallel universes are responsible. With every further observation of interference (stage 3) we become a little more convinced of that theory. After a sufficiently long sequence of such observations, and provided that none of them ever contradicts the theory, we conclude (stage 4) that the theory is true. Although we can never be absolutely sure, we are for practical purposes convinced. — page 59

3.3.3. What is the criticism of induction? Describe an example of the Bertrand Russell chicken.

First, a generalized prediction is rarely a candidate for a new theory and our deepest theories seldom are generalizable. With the multiverse example we certainly have not observed first one universe, then second, then third, and then concluded there are trillions of them! {3.1 Induction and baby weight.}

Second, inductivism uses the same observations to ‘justify’ theories. Consider Russell’s chicken:

The chicken noticed that the farmer came every day to feed it. It predicted that the farmer would continue to bring food every day. Inductivists think that the chicken had ‘extrapolated’ its observations into a theory, and that each feeding time added justification to that theory. Then one day the farmer came and wrung the chicken’s neck. — page 60

Should the chicken believe that its feeding theory would become more certain (i.e. more justified) with each day (observation)? What if the chicken generalized a diametrically opposite theory? The same observations would then support it as well:

However, this line of criticism lets inductivism off far too lightly. It does illustrate the fact that repeated observations cannot justify theories, but in doing so it entirely misses (or rather, accepts) a more basic misconception: namely, that the inductive extrapolation of observations to form new theories is even possible. In fact, it is impossible to extrapolate observations unless one has already placed them within an explanatory framework. For example, in order to ‘induce’ its false prediction, Russell’s chicken must first have had in mind a false explanation of the farmer’s behaviour. Perhaps it guessed that the farmer harboured benevolent feelings towards chickens. Had it guessed a different explanation - that the farmer was trying to fatten the chickens up for slaughter, for instance - it would have ‘extrapolated’ the behaviour differently. Suppose that one day the farmer starts bringing the chickens more food than usual. How one extrapolates this new set of observations to predict the farmer’s future behaviour depends entirely on how one explains it. According to the benevolent-farmer theory, it is evidence that the farmer’s benevolence towards chickens has increased, and that therefore the chickens have even less to worry about than before. But according to the fattening-up theory, the behaviour is ominous - it is evidence that slaughter is imminent. — page 60

Depending on the chicken’s mood when farmer first time brought more food it would conclude that either it is about to die, or live a happy, long life. Induction provides no mechanism to distinguish theories.

Popperian Epistemology

3.4.0 What is the Popperian epistemology?

A philosophical theory that science is a problem-solving process. The problem arises when our current theories seem inadequate.

By a ‘problem’ I do not necessarily mean a practical emergency, or a source of anxiety. I just mean a set of ideas that seems inadequate and worth trying to improve. The existing explanation may seem too glib, or too laboured; it may seem unnecessarily narrow, or unrealistically ambitious. One may glimpse a possible unification with other ideas. Or a satisfactory explanation in one field may appear to be irreconcilable with an equally satisfactory explanation in another. Or it may be that there have been some surprising observations - such as the wandering of planets - which existing theories [celestial sphere] did not predict and cannot explain. — page 62

3.4.1 What are the stages of Popperian epistemology?

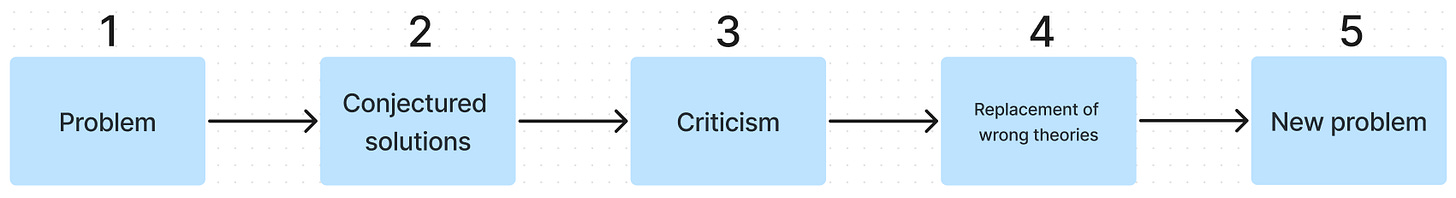

after a problem presents itself (stage 1), the next stage always involves conjecture: proposing new theories, or modifying or reinterpreting old ones, in the hope of solving the problem (stage 2). The conjectures are then criticized which, if the criticism is rational, entails examining and comparing them to see which offers the best explanations, according to the criteria inherent in the problem (stage 3). When a conjectured theory fails to survive criticism - that is, when it appears to offer worse explanations than other theories do - it is abandoned. If we find ourselves abandoning one of our originally held theories in favour of one of the newly proposed ones (stage 4), we tentatively deem our problem-solving enterprise to have made progress. I say ‘tentatively’, because subsequent problem solving will probably involve altering or replacing even these new, apparently satisfactory theories, and sometimes even resurrecting some of the apparently unsatisfactory ones. — page 64

3.2 On further inquiry.

If you’d like to dive-in further I recommend reading The Logic of Experimental Tests.

3.4.2 What fifth stage implies in the Popperian epistemology?

Popperian epistemology regards science as a never ending process, for our knowledge will always be fallible and improvable. Yet in induction we can arrive at the final truth, hence science has an end.

This difference is due to justification, **induction assumes that one can (or needs to) create positive evidence for a theory. But, if we just guess (conjecture) theories (solutions) then we are always fallible, for our senses and tools are so too. Our guesses are always approximations of reality, yet some are better than others, like general relativity and Newtonian physics.

Thus the solution, however good, is not the end of the story: it is a starting-point for the next problem-solving process (stage 5). This illustrates another of the misconceptions behind inductivism. In science the object of the exercise is not to find a theory that will, or is likely to, be deemed true for ever; it is to find the best theory available now, and if possible to improve on all available theories. A scientific argument is intended to persuade us that a given explanation is the best one available. — page 64

3.5.0 What is a crucial experimental test?

The distinguishing characteristic between scientific problem-solving is the use of experiments to rule out opposing theories (stage 3 in Popperian epistemology). How do we know that general relativity is better than Newtonian physics? We create an experiment where theories diverge in their predictions and then conduct it. Its outcome would refute one of the theories, so we conclude that the last man standing is our best explanation of reality, so far. It is a mistake to say that general relativity has been justified by the experiment, its outcome is just in-line with what the theory predicted. It doesn’t imply that the theory is the ultimate truth. In fact, theories can never be the ultimate truth, because they all are just our guesses, and we are fallible.

Scientific problem-solving always includes a particular method of rational criticism, namely experimental testing. Where two or more rival theories make conflicting predictions about the outcome of an experiment, the experiment is performed and the theory or theories that made false predictions are abandoned. The very construction of scientific conjectures is focused on finding explanations that have experimentally testable predictions. Ideally we are always seeking crucial experimental tests experiments whose outcomes, whatever they are, will falsify one or more of the contending theories. — page 65

3.6.0 What are the similarities between Popperian epistemology and evolution?

Both use error-correction mechanism: variation and selection in evolution, conjectures and refutations in epistemology. Be it scientific theories or genes, the essence of knowledge creation is in error-correction.

While a problem is still in the process of being solved we are dealing with a large, heterogeneous set of ideas, theories, and criteria, with many variants of each, all competing for survival. There is a continual turnover of theories as they are altered or replaced by new ones. So all the theories are being subjected to variation and selection, according to criteria which are themselves subject to variation and selection. The whole process resembles biological evolution. A problem is like an ecological niche, and a theory is like a gene or a species which is being tested for viability in that niche. Variants of theories, like genetic mutations, are continually being created, and less successful variants become extinct when more successful variants take over. ‘Success’ is the ability to survive repeatedly under the selective pressures - criticism - brought to bear in that niche, and the criteria for that criticism depend partly on the physical characteristics of the niche and partly on the attributes of other genes and species (i.e. other ideas) that are already present there. — page 67

3.6.1 What are the differences between Popperian epistemology and evolution?

One difference is that in biology variations (mutations) are random, blind and purposeless, while in human problem-solving the creation of new conjectures is itself a complex, knowledge-laden process driven by the intentions of the people concerned. Perhaps an even more important difference is that there is no biological equivalent of argument. All conjectures have to be tested experimentally, which is one reason why biological evolution is slower and less efficient by an astronomically large factor. Nevertheless, the link between the two sorts of process is far more than mere analogy: they are two of my four intimately related ‘main strands’ of explanation of the fabric of reality. — page 68

💤 4 — Criteria for Reality

When arguing for the multiverse world-view we have inexplicitly rejected a set of ‘solipsistic’ theories, while subscribing to realism. It is time to test that assumption.

Summary

Realism is the view that reality objectively exists, regardless of a subjective observer. Meaning, the chair you are sitting would still exists regardless of your looking at it or not.

Solipsism is the view that there is some boundary to reality, like that it is all a matrix, or a dream in your head. It is hard to disprove for every prediction it makes would also be in line with realism. So how do we distinguish the two?

Through a philosophical argument. Solipsism is wrong because it is easy to vary, it has one needless assumption that it’s all just a dream, or a matrix. This assumption is easy to vary, so we can fill-in the blank whatever we want, like: “It’s a matrix with two computers, not one! The second one running specifically for Chinese due to their firewall!”.

The same way we can distinguish between heliocentric (Earth moves around the Sun) and geocentric (everything moves around the Earth) theories. Geocentric theory make a needless assumption that is easy to vary, yet with heliocentric remove one note and harmony will fall.

Something is real or not if it is in our best explanations of reality.

You can practice chapter questions as flashcards here.

4.1.0 What is realism?

A view that reality objectively exists, regardless of any subjective observer. This means that the chair I am sitting on actually exists, and if I go to the cinema it would still exist, even though I won’t observe it. I don’t observe the computer you are reading this from, but your computer still exists.

The theory that an external physical universe exists objectively and affects us through our senses. — page 96

4.2.0 What makes solipsism hard to disprove?

Solipsism is problematic because one cannot empirically disprove it. Any observational evidence you collect is ‘in-line’ with the theory that you have dreamt it. So if you say that according to realism the ball should drop, then solipsism would say: “Just as you have said it, BUT! it’s all a dream (or matrix and so on).”. Any prediction you make, solipsism would make the same but with one additional assumption — it’s all just a dream (or matrix and so on). {Remind yourself what solipsism is in card 3.1.0}

[solipsism] cannot be logically disproved. Reality might consist of one person, presumably you, dreaming a lifetime’s experiences. Or it might consist of just you and me. Or just the planet Earth and its inhabitants. And if we dreamed evidence - any evidence - of the existence of other people, or other planets, or other universes, that would prove nothing about how many of those things there really are. — page 58

As we have mentioned solipsism is an umbrella term, for it could be used to describe a set of philosophies that make the same predictions as realism, but then draw an arbitrary boundary of existence (make just one more assumption). Instead of saying “it’s all just a dream”, some would say “it’s all just a matrix”, or reason has no value from here and on.

4.3.0 How can we disprove solipsism?

As we have shown, solipsism is immune to the experimental criticism — any observation is in-line with it. So how could we disprove it? {4.2 On hierarchy of criticisms. David explains that philosophical arguments are just as effective as experimental or mathematical ones. In fact, there is no hierarchy of proves, one should seek good explanations on any ‘level of sciences’; hopefully you remember this from the first chapter!}

We appeal to the philosophical argument! {4.3 On presented arguments. Important note: this is not the reason that David presents in the Fabric of Reality, we refute solipsism by his latest epistemological breakthrough of the ‘hard to vary’ criterion.}

The purpose of science is to understand the reality, we do so by explaining it. In science we search for good explanations. In his last book: The Beginning of Infinity, David makes an epistemological breakthrough by defining criterion for good explanations. Good explanations are hard to vary.

If we want to explain reality we have to be cautious with what we include in our explanations, one could rephrase Occam’s razor as:

Do not complicate explanations beyond necessity, because if you do, the unnecessary complications themselves will remain unexplained. — page 78

Hence our criticism of solipsism is twofold. First, the assumption that this is all just a dream has no good (hard to vary) explanation behind it, we just as successfully could say it is a matrix. Second, this additional assumption leaves more unexplained than explained: Where are you sleeping? How come you dream for so long? Why are you alive? Are the things that are not yet known to you, actually part of your brain (like quantum physics, or content of the next chapters 😉)? Same questions would apply to the matrix assumptions: Where is the computer? How it works? Who controls it? Can we escape it? Why they run it?

We have no observational evidence to conclude this is not a dream or matrix. But if we want to understand reality, we must search for hard to vary explanations. Any solipsism variation is just a realism with an additional assumption that is left unexplained and easily varied.

Thus solipsism, far from being a world-view stripped to its essentials, is actually just realism disguised and weighed down by additional unnecessary assumptions - worthless baggage, introduced only to be explained away. — page 83

4.4.0 What are the heliocentric and the geocentric theories?

heliocentric theory The theory that the Earth moves round the Sun, and spins on its own axis.

geocentric theory The theory that the Earth is at rest and other astronomical bodies move around it — page 96

David goes in great detail explaining the differences between the two in the book. The essence of it is:

The heliocentric theory explains them [planetary motions] by saying that the planets are seen to move in complicated loops across the sky because they are really moving in simple circles (or ellipses) in space, but the Earth is moving as well. The Inquisition’s explanation is that the planets are seen to move in complicated loops because they really are moving in complicated loops in space; but (and here, according to the Inquisition’s theory, comes the essence of the explanation) this complicated motion is governed by a simple underlying principle: namely, that the planets move in such a way that, when viewed from the Earth, they appear just as they would if they and the Earth were in simple orbits round the Sun.

To understand planetary motions in terms of the Inquisition’s theory, it is essential that one should understand this principle, for the constraints it imposes are the basis of every detailed explanation that one can make under the theory. For example, if one were asked why a planetary conjunction occurred on such-and-such a date, or why a planet backtracked across the sky in a loop of a particular shape, the answer would always be ‘because that is how it would look if the heliocentric theory were true’. So here is a cosmology - the Inquisition’s cosmology - that can be understood only in terms of a different cosmology, the heliocentric cosmology that it contradicts but faithfully mimics. — page 78

4.4.1 How do we choose between them?

Just as with solipsism we can’t apply experimental criticism since theories make equal predictions:

If the Inquisition’s theory were true, we should still expect the heliocentric theory to make accurate predictions of the results of all Earth-based astronomical observations, even though it would be factually false. It would therefore seem that any observations that appear to support the heliocentric theory lend equal support to the Inquisition’s theory. — page 77

As with solipsism we must apply the ‘hard to vary’ criterion. The assumption that planets move as if around the Sun, but they don’t and actually the Earth is at rest is — unexplained. More precisely, to understand Inquisitions theory we must first understand heliocentric theory, and then add an unnecessary assumption:

If the Inquisition had seriously tried to understand the world in terms of the theory they tried to force on Galileo, they would also have understood its fatal weakness, namely that it fails to solve the problem it purports to solve. It does not explain planetary motions ‘without having to introduce the complication of the heliocentric system’. On the contrary, it unavoidably incorporates that system as part of its own principle for explaining planetary motions. One cannot understand the world through the Inquisition’s theory unless one understands the heliocentric theory first.

Therefore we are right to regard the Inquisition’s theory as a convoluted elaboration of the heliocentric theory, rather than vice versa. We have arrived at this conclusion not by judging the Inquisition’s theory against modern cosmology, which would have been a circular argument, but by insisting on taking the Inquisition’s theory seriously, in its own terms, as an explanation of the world. — page 79

It is not that the heliocentric theory is right because it is simpler, or more intuitive. To claim that the Earth is moving is a counter-intuitive assumption. The difference is that Galileo explains why it feels like it’s at rest, and why it’s actually moving. On the other hand, Inquisition’s assumption is not explained, it is just postulated, and hence, easy to vary. We could say that the stars moves as if around the Sun, but actually its Jupiter that is at rest, not Earth.

4.5.0 How do we know whether something is real? What is the criteria for reality?

{4.4 On criterion changes. David defines the criteria in the Fabric of Reality which he improves upon in the Beginning of Infinity. I present his latest version. The old criterion is:

Dr Johnson’s criterion (My formulation) If it can kick back, it exists. A more elaborate version is: If, according to the simplest explanation, an entity is complex and autonomous, then that entity is real. — page 96 }

Something is real or exist as long as it appears in our best explanations of reality. This criterion applies to the example that David gives:

If you feel a sudden pain in your shoulder as you walk down a busy street, and look around, and see nothing to explain it, you may wonder whether the pain was caused by an unconscious part of your own mind, or by your body, or by something outside. You may consider it possible that a hidden prankster has shot you with an air-gun, yet come to no conclusion as to the reality of such a person. But if you then saw an air-gun pellet rolling away on the pavement, you might conclude that no explanation solved the problem as well as the air-gun explanation, in which case you would adopt it. In other words, you would tentatively infer the existence of a person you had not seen, and might never see, just because of that person’s role in the best explanation available to you. Clearly the theory of such a person’s existence is not a logical consequence of the observed evidence (which, incidentally, would consist of a single observation). Nor does that theory have the form of an ‘inductive generalization’, for example that you will observe the same thing again if you perform the same experiment. Nor is the theory experimentally testable: experiment could never prove the absence of a hidden prankster. Despite all that, the argument in favour of the theory could be overwhelmingly convincing, if it were the best explanation. — page 90

🧠 5 — Virtual Reality

David explains that human brain is like a virtual reality machine because we can render environments, both real and imaginary. Our perception of the world is a virtual reality created by our brain from its sensory inputs. Understanding involves comparing our reality with the external one; through scientific method we can improve our accuracy. This analogy makes it obvious that our reality is always fallible and inaccurate, for we don’t receive it from some ‘ultimate source’ — it is just our senses and guesses.

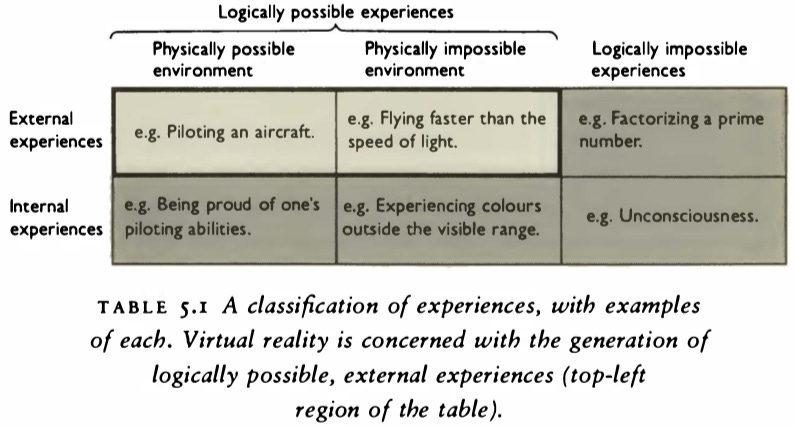

The main question of the chapter is: